Director Todd Haynes may have made his name with a series of sly, sublime, and pop-savvy New Queer Cinema profiteroles like Poison, Velvet Goldmine, and Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, but in recent years he's resurrected the forgotten genre of what Old Hollywood called "women's pictures": lachrymose melodramas in which glamorous ladies struggle with the pain and sacrifice of human relationships, snatching morsels of joy for themselves (as permitted by a sexist society's constrictive rules) when they aren't weeping bitter tears discreetly into their handkerchiefs. His first foray into this style, Far From Heaven, was half homage to women's picture king Douglas Sirk, half postmodern chiding of the genre's limitations, but after readapting Mildred Pierce into a compulsively watchable miniseries on HBO, Haynes is ready to play it straight.

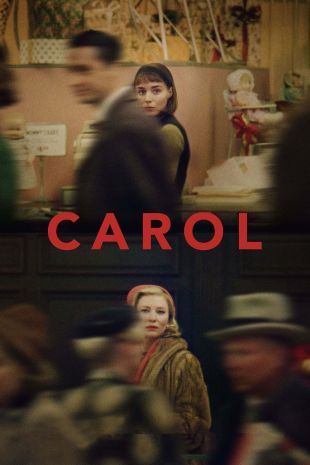

Or not straight, as it were. Carol (née The Price of Salt) is the most autobiographical of Patricia Highsmith's novels, dealing so frankly with her own lesbian experiences that she originally had it published under a pseudonym. As with Mildred Pierce, Haynes sticks fairly closely to the novel's original plot. Therese (Rooney Mara) is an owl-eyed shopgirl at a department store in 1950s Manhattan. One afternoon, elegant society dame Carol (Cate Blanchett) stops by the toy counter, her coiffure and fur coat almost the same color of honey blonde. She wants to know: What kind of doll would a little girl want? This Christmas she's estranged from her husband (Kyle Chandler) and needs the perfect present to make the holiday separation as painless as possible for their daughter (Kk Heim). Maybe Carol leaves her kidskin gloves on the counter by accident, or maybe not. But Therese takes the bait and, after looking up her address on the sales slip, mails them to her in New Jersey. A few days later the women are having lunch together and making plans to visit Carol's comfortable suburban home. "What a strange girl you are," the much older Carol purrs to Therese from behind a scrim of cigarette smoke, "flying out of space."

Haynes takes great pleasure in nailing every period detail in his movies, and he's chosen an atypically bleak view of the 1950s that's arguably more accurate than the pastel-colored Googie style typically used to represent an era that's more restrictive and conformist than we'd like to remember. Therese's world is chintzy and utilitarian, with Soviet-like vinyl floors and slush in her boots, and her apartment is so cold in the mornings that she has to light the gas in her kitchen stove to warm the space before she can brush her teeth. The accumulated discomforts of her life stand in stark contrast to the middle-class luxuries -- tailored dresses, carpeted floors, phonographs, and fireplaces -- that Carol is entitled to in her final days as someone's wife. All of these stark details underline how Haynes refuses to let us get misty-eyed about the real stakes of our heroines' situation: The velvet-lined coffin of a life pretending to be heterosexual is still a much needed shelter from a brutal world. Both women are needy and confused in different ways, and perhaps they're not really suited for each other. Is the much older Carol predatory in her unhurried seduction of Therese? She's certainly hungry for something; both women are. She doesn't intend to lure Therese in and use her up and ruin both their lives, but she might not be able to prevent this outcome, either.

Yet despite being a tragic vignette about the lives of two women, this movie is not a tragedy. (There's no way Joan Crawford or Barbara Stanwyck would ever have been allowed to touch this material during the golden age of women's pictures, but their loss is Blanchett and Mara's gain.) Even though Therese and Carol's intimate connection -- it's not quite fair to call it "love" -- can only expand so far inside the confines of their society (and the guillotine blade falls swiftly when its bounds are overstepped), they are ultimately triumphant -- maybe not at the end of this film, and maybe not in each other's arms, but as people growing through suffering and finding grace in who they really are, the world be damned. That's better than a doll for Christmas any day.