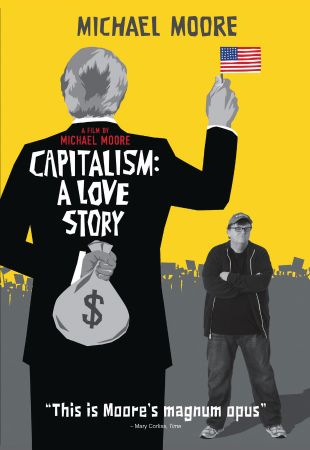

Since the release of Roger & Me in 1989, Michael Moore's name is rarely heard in the media without the preface of "controversial filmmaker" -- and that's when they're being kind. Less receptive outlets tend to use terms like "left-wing lightning rod," and, occasionally, "lying bastard." With a 20-year career that's taken on some of the most polarizing issues in the United States, Moore's reputation as an incendiary liberal isn't surprising, nor is it undeserved. While that reputation has made it difficult for his films to garner an objective reception, they've rarely, if ever, been boring. Bearing that in mind, the premise of Capitalism: A Love Story -- two hours dedicated to the evolution of economic theory between 1932 and 2008 -- threatens to be at least a little tedious. Any trepidation one might have going into the film, however, is unwarranted. Capitalism passionately incorporates elements from virtually all of Moore's past efforts, from poor health care and mass layoffs to the devastation of being evicted from one's home, giving it a cohesiveness that makes for a movie as inspiring and forceful as anything the director has done in his past. While it's unlikely that this will be Moore's last documentary, it feels like an opus, or, less dramatically, the end of an emotionally charged cross-country road trip that began and ended in Flint, MI, peppered with unsuccessful attempts to get inside the headquarters of General Motors.

Though less focused than Bowling for Columbine or Fahrenheit 9/11, the film is never scattered. Whether lampooning the abysmal wages of airline pilots or following a Peoria couple through a gut-wrenching home foreclosure process, the message is consistent: capitalism has been distorted from the free enterprise it used to represent into a cartel comprised of America's wealthiest industries and individuals, whose shared goal is to continue amassing wealth for themselves, at the financial and spiritual cost of average Americans. According to Moore, the so-called socialism that this top one percent of society is so adamantly against is not a form of liberal extremism bordering on fascism, but a true democracy in which all Americans are able to share in America's wealth -- and that America's wealth isn't limited to money in the bank. Moore posits that this brand of democracy began to deteriorate after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the consequent death of his proposed Second Bill of Rights, which would have given all Americans the right to health care, a living wage, and a decent home (ironically, members of FDR's administration would implement many of these policies in Europe during its reconstruction after WWII). The second factor, in an eerie echo of Roger & Me, was the election of Ronald Reagan. In an interview, former U.S. banks regulator Bill Black implies heavily that Reagan's presidency caused a "seep in the dam" that eroded through the years and finally broke in 2008, nearly taking America's economy with it.

Moore's solution, unfortunately, is a little too simple. All society needs to do, he says, is organize, strike, rally, and vote against the industries responsible for depriving them of what FDR considered basic American rights. It's not that the sentiment is untrue, or that his examples of such movements aren't inspiring -- they are -- but they feel like a drop in the bucket. Though the film doesn't suggest that a large-scale revolution is easy, neither does it impart how monumentally difficult such an undertaking would be. Then again, footage capturing the laid-off employees of SK Hand Tools' victory after a long battle with financial powerhouse Bank of America brings something to the table that may, in the long run, be more effective than the gritty realities of causing nationwide political upheavals: hope. If a factory of working-class citizens can stick it to corporate America, maybe the good guys can win in the end. Sure, it's idealistic -- but in a post-bailout America, even a drop in the bucket goes a long way.